Overview

The NSW Government has launched Dine & Discover NSW to encourage the community to get out and about and support dining, arts and tourism businesses.

NSW residents aged 18 and over can apply for 4 x $25 vouchers, worth $100 in total.

- 2 x $25 Dine NSW Vouchers to be used for dining in at restaurants, cafés, bars, wineries, pubs or clubs.

- 2 x $25 Discover NSW Vouchers to be used for entertainment and recreation, including cultural institutions, live music, and arts venues.

The Vouchers

There are two ways to access these vouchers:

- Email – Vouchers are initially emailed to eligible participants of the program after they sign up.

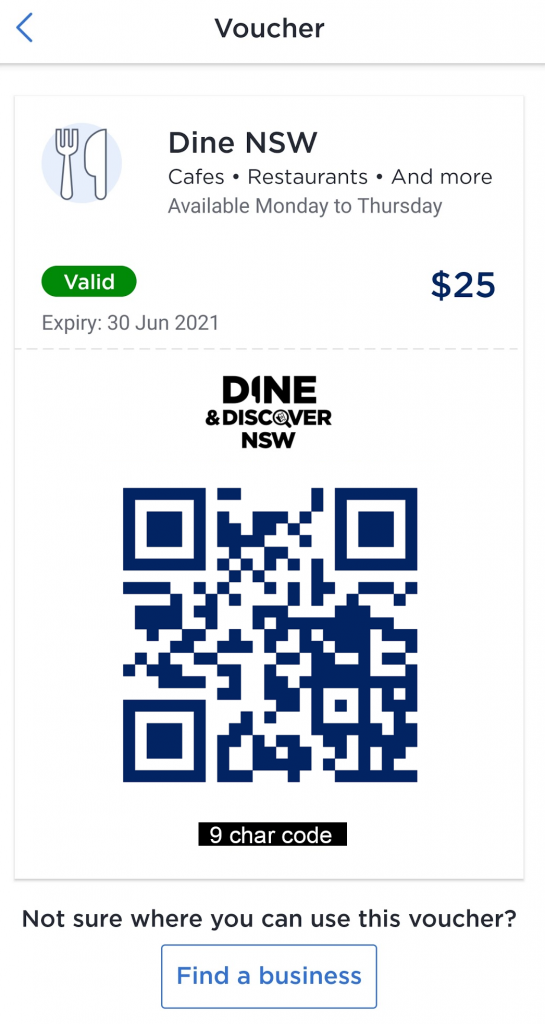

- ServiceNSW App – Vouchers can be accessed from the ServiceNSW

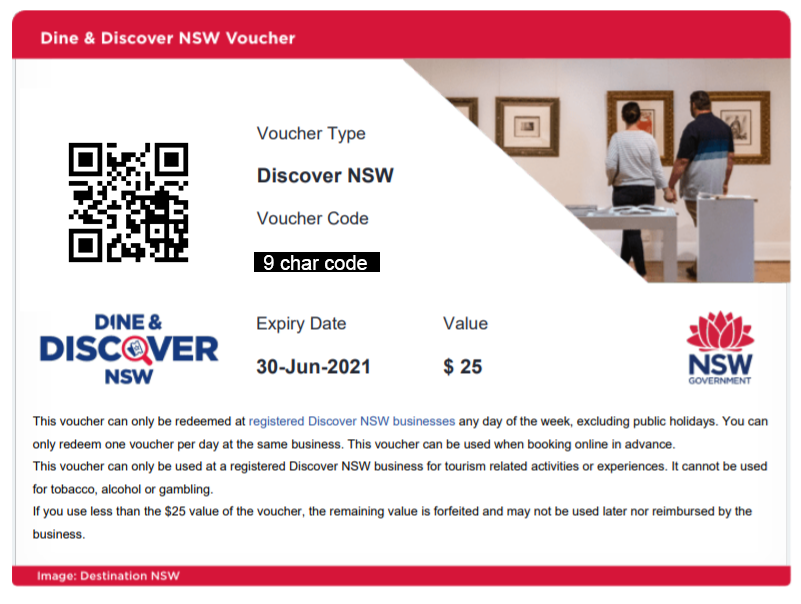

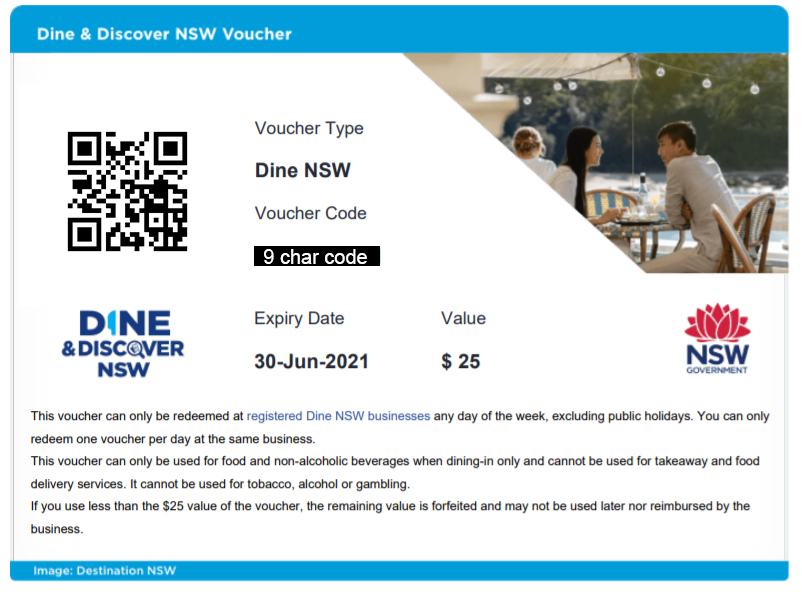

The initial email contains a PDF attachment that contains vouchers that look like this:

Each voucher has a few pieces of metadata attached:

- The voucher type (Dine or Discovery)

- A 9 character voucher code such as ED04K31MB (omitted from screenshots above)

- A QR code with embedded data

- An expiry date (in this case 30-Jun-2021)

- Value (in this case $25)

Using the vouchers

There are two ways you can redeem your vouchers online or in-person:

- You can supply a participating business with your 9-char voucher code such as ED04K31MB

- You can show a participating business the QR code which exists to promote COVID-safe contactless interactions.

Email Vouchers vs ServiceNSW App Vouchers Discrepancy

There appears to be a discrepancy between the voucher codes and QR codes sent in the original email and the ones that appear in the ServiceNSW mobile app. The codes sent in the email seem to be the original codes and are “long life”. The codes generated in the ServiceNSW app seem to be generated each time you click on a voucher. They are likely temporary codes that, in the end, are all linked back to the unique identifier for your voucher. So once you use the code in the email or any code generated by the app, your uniquely identified voucher will be marked as used.

I didn’t test using old codes though but I’ll give ServiceNSW the benefit of the doubt here. 😉

Voucher format

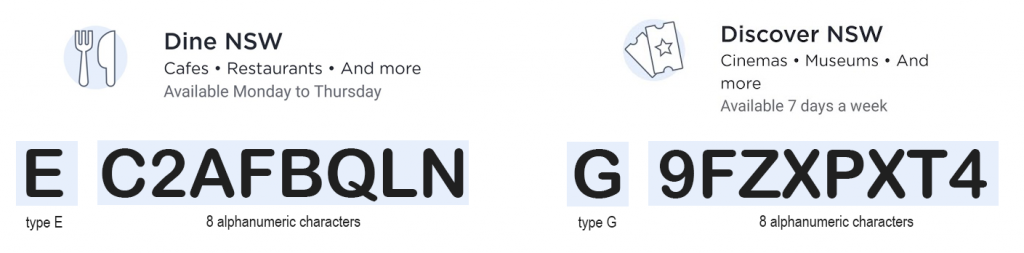

Each voucher is 9 characters in length.

Discovery vouchers always start with the letter G. Dine vouchers always start with the letter E.

The remaining 8 characters seem to be random alphanumeric characters (case-insensitive).

That QR code though…

Scanning any of the voucher QR codes gives us some plain text.

Dine/Discover Voucher (ServiceNSW App)

For example here is the output from scanning a Discover voucher from the ServiceNSW app:

|

1 |

eyAidiI6eyAiZCI6IjVabGZRVW9paXhOMjhhQnAiLCAidCI6IkNTRyIgfSwgInRzIjoiMjAyMS0wMy0yNVQwODoxNTowNy40MTBaIiwgIm0iOiIyNDgzZmQ4YmQ3NWUxYTE5ZjdiZDk1NzdkMjg2ZTJlOGEyMWMzNDQ5YWUzYjQxZDIzNWYxMjNjODhjODI1ZWY5IiB9 |

This is a Base64 encoded string that represents the following JSON object:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 |

{ "v":{ "d":"5ZlfQUoiixN28aBp", "t":"CSG" }, "ts":"2021-03-25T08:15:07.410Z", "m":"2483fd8bd75e1a19f7bd9577d286e2e8a21c3449ae3b41d235f123c88c825ef9" } |

We have a few fields present:

- v: voucher

- d: data – the first 8 characters here appended to G or E (based on type) to create the voucher code; it is unclear what the last 8 digits represent (checksum or additional code?)

- t: type of voucher, either CSG (for discovery vouchers) or CSE (for dine vouchers)

- ts: timestamp – ISO8601 time string representing the time the voucher code was generated

- m: unknown – as a 64 character hexadecimal hash it may be a SHA256 hash but I am not sure what it could represent (perhaps member?)

Dine/Discover Voucher (Email)

Interestingly, the QR code output from the vouchers in the email is different.

For example here is the output from scanning a Dine voucher from the email:

|

1 |

eyJ2Ijp7ImQiOiIwNGMyNjgzYy1iYmYzLTYyOWItYjUxYy0wMTI2YzNiNTNkOTMiLCJ0IjoiQ1NHIn19Cg== |

This is a Base64 encoded string that represents the following JSON object:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

{ "v":{ "d":"04c2683c-bbf3-629b-b51c-0126c3b53d93", "t":"CSG" } } |

We have a few fields present:

- v: voucher

- d: data – this appears to be the unique identifier of our voucher in UUID format (which is what the temporary voucher/QR codes from the ServiceNSW app are likely linked to)

- t: type of voucher, either CSG (for discovery vouchers) or CSE (for dine vouchers)

Notice how the ts (timestamp) and m (unknown) fields are missing here.

Third-Party Validation API

The obvious attack vector here is the participating businesses that accept these codes. There is likely a private API exposed by ServiceNSW and provided to participating businesses to validate and use these vouchers. I discovered that Hoyts (a participating business) was using this API behind the scenes through their own API proxy here:

https://store.hoyts.com.au/payments/snsw-voucher-checkout?voucher=EXAMPLE

This API takes a voucher code and returns a few responses based on the result of the validation.

Valid (unused) voucher:

|

1 2 3 4 |

{ "CardNumber": "GEXAMPLE1", "Amount": 25.0 } |

Valid (unused) voucher but the user has already redeemed voucher at this business during this business day:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

{ "Status": "RequestError", "Messages": [ "\"This customer has already redeemed voucher with this business today\"" ] } |

Valid (unused) voucher but wrong type:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

{ "Status": "RequestError", "Messages": [ "\"The specified Dine voucher cannot be used.\"" ] } |

Invalid (already used) voucher:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

{ "Status": "RequestError", "Messages": [ "\"The voucher has been used\"" ] } |

Invalid (not found) voucher:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

{ "Status": "RequestError", "Messages": [ "\"The voucher specified could not be found\"" ] } |

Invalid (wrong format) voucher:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

{ "Status": "RequestError", "Messages": [ "An unexpected error occurred while validating voucher. Please try again later." ] } |

Bruteforce attack

Each voucher code is 9 characters long. As the first character is hardcoded, this leaves only 8 characters. It appears that the next 8 characters are random alphanumeric characters. Furthermore, by testing an API we discover we can confirm that upper and lowercase characters are equivalent. In other words, the voucher codes are case insensitive.

This leaves us with a character set of 36 characters (26 letters of English alphabet + 10 digits):

|

1 |

abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz0123456789 |

There are roughly 8 million residents in NSW. Modestly assuming 60% of those are adults over 18 and eligible for the NSW Dine & Discover voucher program, there are potentially up to 4.8 million vouchers originally generated and sent to a users email address. However, the total number of unique 8 character combinations with the above character set is 36 pick 8, or 2 821 109 907 456 (~2 trillion). Double that for each voucher type. That means that at best only 0.0001701% of the maximum combinations will be valid voucher codes for each voucher type. We are ignoring the temporary generated voucher codes here as they may expire and are likely not frequently generated until just before they are used.

If this were a password hash, with only 8 characters of entropy and a 36 character set, it would definitely be feasible to brute force the entire combination set. 8 character passwords with a character set this small are not secure and can be cracked offline from a hash within 10 – 30 days with moderately cheap hardware.

Unfortunately, though, we are forced to validate our codes online through the Hoyts API. This is much, much slower than GPU hash cracking due to the cost of networking and has other unwanted side effects:

- Slow network-based validation technique

- Raising suspicion by server maintainers through metrics they collect around API usage

- Bringing additional load onto Hoyts servers and by extension ServiceNSW servers

- Running into rate limiting issues (severely reducing the effectiveness of our brute force attack)

Bruteforce attempt and results

Nevertheless, in the spirit of giving it a go and in good faith I attempted a hopeless brute force attempt. I started a cluster of AWS lambdas in the ap-southeast-2 region running a simple Python scraping script. For simplicity, I logged any unexpected API responses to Cloudwatch. This code will not be released publically for obvious reasons. Furthermore, I time-boxed this experiment to only 12 hours as I would prefer to not needlessly burn money through AWS fees.

Unsurprisingly, I found no other valid voucher codes and that is good news for everyone.

Now get out there and kick start NSW again!